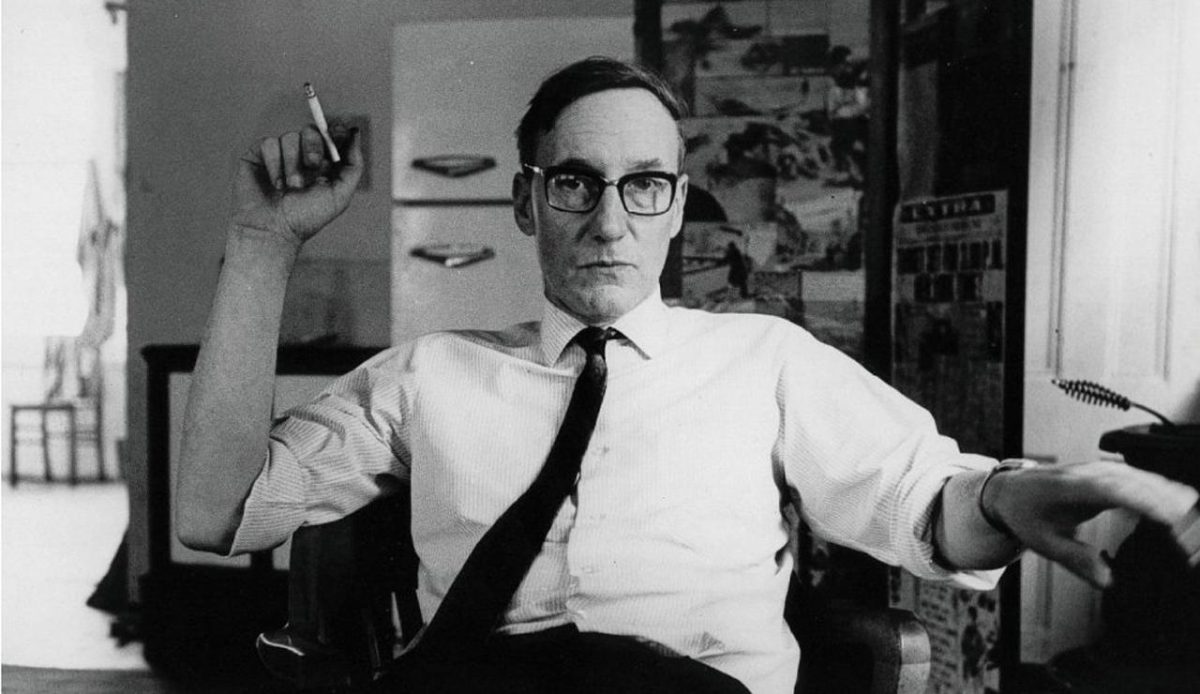

In the mid-1950s, a group of forward-thinking young writers took the American literary scene by storm. They began to write poetry, memoirs, and works of fiction characterized by their progressive perspectives on drugs, sexual orientation, and religion, as well as their pioneering use of nontraditional writing techniques. These often controversial legends of 20th century American literature made up what came to be known as the Beat Generation, comprised of such literary powerhouses as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Herbert Huncke, John Giorno, and many others. One of the most prolific members of the Beat Generation, whose influence on popular culture is still very much felt today, is William S. Burroughs, most well known for his challenging and controversial novel “Naked Lunch,” published in 1959 to critical praise and moral outrage. “Junky,” Burroughs’ first published work, is a memoir of sorts, detailing Burroughs’ own experiences with heroin addiction and the state of contemporary drug culture in various locales ranging from New York City to Mexico City.

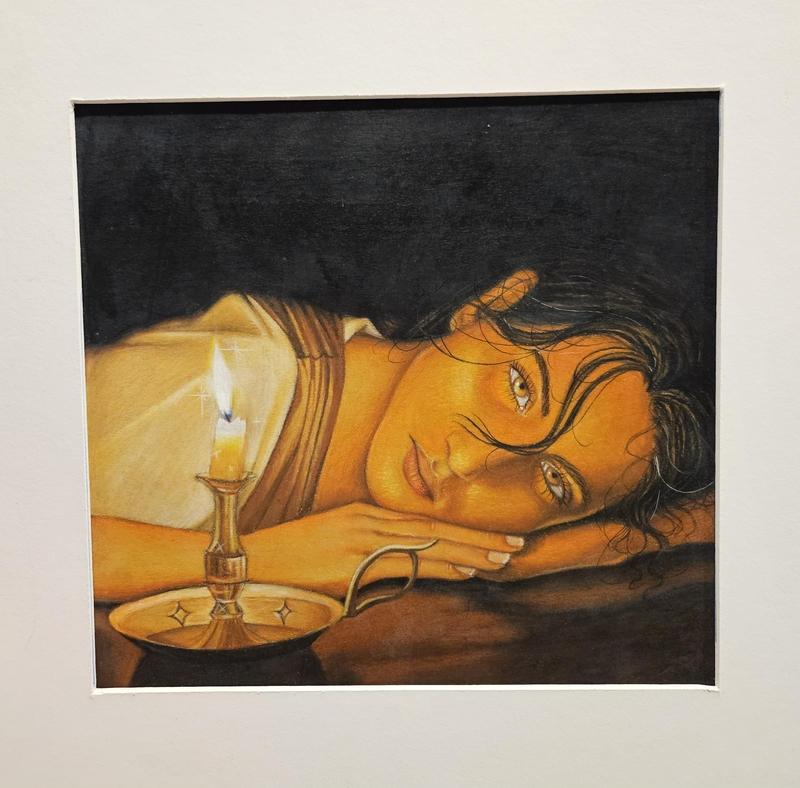

Noted for its precise, unadorned prose, “Junky” is stylistically a far cry from Burroughs’ later works, yet marks the beginning of many themes that run through the rest of his oeuvre. Burroughs’ writings on his narcotics experimentation, distrust of authority, and intermixing with queer culture all get their start with this book. The beginning of “Junky” closely follows Burroughs’ real life and briefly details his high-class upbringing as the heir to a family fortune in St. Louis. Following a period of taking university courses in Europe and drifting around the globe, sustained on his family trust, Burroughs has his first run-in with opiates in New York City, quickly developing a morphine addiction and befriending a large group of other opiate addicts. It soon becomes apparent that he and the other addicts will do anything to get the money for a fix, whether it’s “rolling a lush” (robbing an intoxicated person), “making cars” (breaking into parked vehicles), or “taking care of someone” (selling junk to another user). They also try to con their way into a fix, often “making a croaker for a script” (lying to a doctor to obtain a prescription). After a series of wild misadventures and close calls with the law, Burroughs kicks his habit and goes clean, moving to New Orleans after the completion of his methadone treatment. There he finds himself catching yet another habit and is forced to sell junk to maintain it, but he can hardly break even as his buyers always ask for credit and short him on his payment. An arrest from the feds gives him a spook and he escapes to Texas where he tries to grow cotton. Unsatisfied with the results, he ends up in Mexico City on the run, where he nearly dies of alcohol abuse. To end the book, he muses about the hallucinogenic drug yage, hoping that it will fill the gap in his life that junk cannot fill.

The biggest takeaway I had from the book was that drug criminalization is a totally ineffective way of trying to curb addiction. All of the addicts in the book’s most significant problems arise from an inability to acquire the junk that they need in order to function–they steal, they lie, and they cheat in order to get it. And they are able to get their fix–in limited quantities, yes, but they are still able to get it despite drug laws forbidding the drug’s sale and distribution. I feel that if these narcotics were legalized and made easily available, the addicts in the book would be much better off and able to function to their fullest capacity.

Something I found interesting was Burroughs’ intense homophobia, despite him often recounting his relations with other men on the same page. He refers to gay men by a number of slurs, calls them “ventriloquists’ dummies,” and attacks their femininity. Yet, he himself is gay! This sort of feminine discrimination amongst gay men, itself an extension of misogyny, is commonplace in the gay community today, and it’s both thought provoking and disheartening to see it pervade even in the 1950s.

Overall, I really enjoyed reading “Junky” and I’m excited to explore Burroughs’ later work in the future. I feel that this is a good primer before diving into his more challenging books. I most enjoyed his descriptions of how drug addiction affects the body and his descriptions of his time in New Mexico. I would give the book four stars out of five and recommend it to anyone interested in Beat Generation literature or a comprehensive guide to heroin addiction and drug culture in the 1950s.